Topic: Violet Evergarden: Eternity and the Auto-Memory Doll piece [Hi!]

(Hi everyone! Couldn't get into the site for a long while but Teague unfucked things, so I'm back. And just wrote the longest piece of film crit I've ever attempted, for a movie that means a whole lot to me. Can't wait to catch up and get back into the swing of things—hope you all are well!)

- - -

Since coming out, in attempts to make family members meet me halfway, I tell them that “I’m still me.” In a technical sense, sure, whatever. But in truth, when I think of my pre-transition self, I think of Philip K. Dick’s VALIS and its description of Horselover Fat’s suicidal friend Gloria: “Fat heard in her rational tone the harp of nihilism, the twang of the void. He was not dealing with a person; he had a reflex-arc thing at the other end of the phone line.”

In my case, that reflex manifested in relentless negative feeling. My pre-transition self was driven by fear and resentment—relationships were transactional, something that I was terrified of losing at any time. Inconveniences were met with quiet seething, setbacks with all-consuming anxiety. I defined other people solely by how they made me feel, and if they made me happy, I immediately became paranoid that they would leave. Kindness was not an end to itself—it existed to buy affection, to make people feel indebted to a friend they would otherwise forget.

If asked, I would have told you I had people I loved. I maybe would have believed it.

---

“I have feelings,” Violet Evergarden tells her colleagues at the postal service in the series’ final episode, as she reflects on her life as a child soldier. “I had them, even back then.” As in my case, it’s technically true. But for much of her early tenure at CH Postal Company, emotions are alien to Violet, both others’ and her own. Things like “yearning,” “kindness,” and above all “love” are twisted by her wartime experiences into concepts it’s impossible for her to understand—she perceives all interactions as orders to be obeyed, and her driving motivation is a fear that any sense of external purpose will be taken from her, leaving her to wrestle with feelings she’s been unable to develop past their basest forms.

The story of Violet Evergarden is not the story of a doll becoming a person, of something unfeeling being granted emotion for the first time. But it’s a story of personhood given shape—of a girl who, in defining others’ feelings through the letters she writes on their behalf, is only then able to define her own.

---

When I started hormones, I knew it would be a gradual physical process—changes don’t happen overnight, and I was prepared to wait a long time for breasts and hips to form, hairline to alter, skin to clear. For my emotions, however, I expected miracles. I took my first doses of spiro and estradiol eagerly waiting for the point a few days later where I would feel the euphoria of my brain chemistry adjusting—where I would at last be able to cry after over a decade without doing so. I’d been primed for floodgates to open.

They didn’t, of course. I spent most of my first year on HRT anxiously waiting for my emotions to snap into place, for the clarity of sharply delineated happiness and sadness to replace the flattened toxicity in my head—hoping for a eureka moment that couldn’t possibly exist.

Trans women are often sold a kind of magical thinking. The online community, eager for us to embrace our true selves, waxes poetic about the huge before/after of hormones, as if all our constituent parts can at once shift into a different being through the simple addition of two pills in the morning and two at night. I can only speak for myself, but, while hormones are a blessing, they didn’t kick open any doors. It wasn’t fair of me to expect that of them.

In the absence of miracles, I was left with a longing to feel and a longing to be good. The two, in my mind, were linked. If I couldn’t become a person—couldn’t experience emotions as anything but varying intensities of anxious buzz, couldn’t stop myself from instantly growing hostile behind the mask of my face—how could I be good? If I couldn’t mean kindness, of what value was it?

If my actions were still born of nothing more than that reflex-arc, what use were they to anyone?

---

Violet too, at the beginning of her journey, seeks a cure-all for her confusion, her desperate feeling that something is not right—for the burning that Claudia Hodgins tells her is consuming her body, whether she realizes it or not. She wants to know what “love” means, and is convinced that if she can become an Auto-Memory Doll—one who puts others’ love down on paper—she’ll have the answer within her grasp.

As a character in a melodrama, Violet is afforded greater catharses than it’s possible for most of us to have. What she’s never granted, however, is an answer to that question of love. Far past the point where she has gained fame for love letters she has written, the word still haunts her. Her job is to express the love of others with a clarity they themselves cannot, all the while still wishing to understand it herself.

To fulfill her duties, she falls back on analogy, pattern recognition, and repetition, taking others’ behavior and words and extrapolating them into feelings. Of course, it doesn’t always work, especially early on when Violet is confined to largely literal thinking. As she says to her coworker Iris, “I thought I had come to understand emotions better . . . but people have very complex and sensitive emotions. Not everyone can express how they truly feel. They end up contradicting themselves or lying, which makes it very difficult for me to understand what’s true and what’s not.” For a girl whose whole existence has been receiving and carrying out orders, the process of deducing from others’ contradictory behavior what they feel, desire, yearn for, is a quagmire. Violet’s journey over the course of the series is the process of fine-tuning her ability to perceive meaning through obfuscation, signal through noise, and thereby write what her clients feel rather than what they say.

By recognizing the patterns in others’ emotions, she begins to see them within her own. She can be angry and recognize her anger for what it is; she can appreciate others’ grief, and cry her own tears when she understands that she too is grieving. But even then, her greatest fear is that information processing is all that’s taking place—when she’s scornfully told all she wants is orders, she insists it’s not true, but still she clings to commands. Order leads to action, A to B, circumstance to the “correct” emotion.

By the main series’ conclusion, Violet has convinced doubters that she is more than an unfeeling toy, and she’s come to understand love well enough that she’s able to claim it for herself—she loves Major Gilbert, who gave her a chance to live. But never once is there a moment where that understanding clicks neatly into place. Her quest to know what love truly means will never be over. And from time to time, she’ll still wonder to herself if she’s ever really felt it, or is simply repeating bits and pieces of the letters she’s written for other people.

---

I’m imitative by nature, to a degree that often worries me. When two acquaintances fight over an issue, I tend to be passionately on the side of whoever spoke most recently. My art absorption tends to go broad and not deep, because I don’t have the ability to find and really identify with specific niches; instead I cannibalize others’ recommendations, sometimes tailoring my opinions to match what seems most acceptable in my circles.

At its worst, this can make me feel unmoored, borderless, the confines of my self completely permeable without any solid core to hold their shape. In a more benign sense, it manifests as borrowing. Magpielike, I fold friends’ words into my vocabulary without context, find myself lapsing into their voices on calls, pick up conversational peculiarities.

At its best, this tendency to copy led me to a better understanding of my gender. I never had strong feelings of dysphoria as a kid, and even as a young adult I did not experience transness as a yearning for something as often as an absence somewhere in my psyche. It took watching women on a screen, reading about them in books, to shape my notions of who I wanted to be; it took years of following trans women on Twitter, molding my manner of speech and my art intake to mirror theirs, to understand what I was experiencing (and, like Violet, had been to some degree all along).

Beyond that, I’ve been fortunate enough to know some people whom I can only describe as hyperbolically kind. When I’m at my best—the closest I’ll be to goodness—it’s because I’m able to take the way those people respond to others’ needs and repurpose it, filching comforting questions and reassurances and gestures and plugging them into situations where they best fit. I don’t do well with reading people’s motivations, their feelings, their needs—there are friends I have known for years and still have no clue how to help or really talk to. But I can pretend to be the kind people I know, and sometimes that does the trick. Sometimes it feels helpful.

When I look at other individuals, I see people; when I look at myself, I see a conglomerate of behaviors I mirror. Sometimes that’s draining. Sometimes it’s reassuring. I’ve never fundamentally left behind the act of kindness as button-pushing, but I’ve gotten better at pushing buttons and knowing what to push with—where before the best I could do was foist gifts on friends, trying to purchase their love with tangible desperation, now I can offer comfort, even if I’m clumsy about it. I can do the right thing and keep my negative feelings in check. I can do my best to express the way I feel about others, the way I hope I feel about them even if I fear my own selfishness.

---

In some ways, the primary Violet Evergarden series ends just where it ought to begin. With each person she has met, each bit of emotion she’s managed to map by putting others’ love to paper, she has assembled for herself a fragile sense of self. “I no longer need orders,” she says near the close—but what does a Violet without orders look like? When her purpose is no longer her superior’s, her employer’s, her clients’, but hers , how will she live her life?

It’s fitting that Eternity and the Auto-Memory Doll chooses a lesbian love story for our window into Violet’s life as her own person—a romance that’s never consummated but clearly experienced by both Violet herself and Amy/Isabella, her charge. Violet’s conception of her personal love throughout the primary series is rigidly patriarchal—the Major, its object, is a man decades her senior, who despite his own love for her is complicit in her ongoing abuse at the hands of a war machine. It’s also inescapably bound up in the structure of orders that gave Violet’s life meaning—her love for the Major is tied to the purpose he provided her, to her desire to carry out his commands. Once she’s rejected orders, the first love she finds herself experiencing is that of another girl her age.

In Amy, and in their friendship that ultimately becomes something more, Violet is afforded physical affection for the first time in her life. Her increasing closeness to her friend—gradually sleeping, bathing, and playing with her—is touching even in isolation, but in the context of Violet’s fuller story, seeing her finally able to offer bodily vulnerability and openness rather than instinctively throwing up walls is beautiful beyond my ability to express.

More than that, she’s given the opportunity to express her love in a form of her choosing. She responds to Amy’s wishes, but she also preemptively offers comfort, whether it’s bedtime stories of constellations or a weary, understanding smile when her friend dissolves into frustration. The Violet of Violet Evergarden is primarily reactive in her kindness, responding to cues and requests when they are given; in Eternity and the Auto-Memory Doll, she breaks out of the reflexive and becomes active. Where before Violet would provide others what they asked to the best of her ability, here she’s able to express love that’s unique to her.

It’s the closest we’ve seen Violet come to being happy and fulfilled. A touching coda to her broader arc. And she herself doesn’t believe it’s true.

“Why are you so kind to me when I was being so mean to you?” Amy asks as the two of them lie in bed.

Violet, bewildered, replies, “Am I kind? . . . I am just imitating someone.”

---

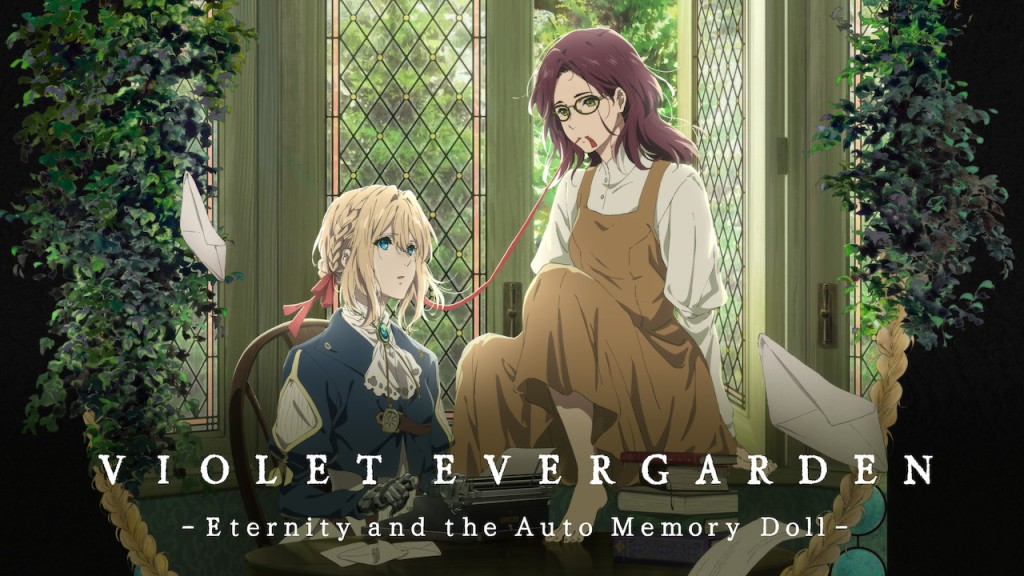

When I first watched Eternity and the Auto-Memory Doll , it was early on in my HRT progress. I came to it blind, with no knowledge of the prior series, and fell totally in love—with Kyoto Animation’s gorgeous realization of the setting, the sweeping romance of Evan Call’s score, and the unabashed period melodrama of the story.

More than any of those, however, I fell in love with Violet. Encountering her in isolation, here at the end of her journey, I saw a person I longed to be—in her physical grace, yes, but mostly in her unwavering goodness toward the people in her care. At the time, she seemed to me to be a model of understanding, something I could aspire to but never achieve.

When I first revisited the film in its proper place as an epilogue (or prelude to an epilogue—as of this writing, the final film has yet to receive a US release that isn’t stymied by COVID), that contextless envy had been replaced by something deeper. I still aspired to be as good as Violet, but I could see bits of myself in her too.

It was only after I started to question my gender that I began trying to imitate love and kindness enough to pass the Turing test. Prior to that point, I was consumed in a feedback loop of selfishness and solipsism. When I realized I wanted to be a girl, I knew I had to start trying.

Even before I knew I was trans, I wanted more than anything to be a lesbian. The picture I would fixate on without comprehending it was myself as a beautiful girl, living with another girl, feeling for the first time emotions I desperately wanted to understand.

That Violet, when she finally chooses a love that is wholly hers, does so with another woman . . . watching it as the endpoint of her story, I told myself that perhaps one day I’d get there.

I want more than anything for Violet to know that she is kind, that she is loving, and that she deserves everything she’s given to others and more. That while her emotion is imitation, it is by no means less real. And I hope that, silly as it sounds, she knows she helped me.

---

A friend of mine gave me permission to share some advice they wrote to their younger self several years ago.

“You're not a sociopath, you're just not good at imagining the complexity of others. Keep mental notes on what you've learned about who someone is, and respectfully try to sort out the things they're most afraid of and most desire. You'll eventually understand them much better than you can imagine right now. People-who-are-good-at-people aren't psychic, they just do this automatically. You have to try. ”

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to conceive of myself as a truly loving or kind person. I live inside my own head too much—I experience all the knee-jerk resentment and hostility that runs through my mind, know which choices have selfish motivations. I’m keenly aware of how many of my actions are made not because I truly mean them but because I hope that, if I repeat them often enough, I’ll become good.

My womanhood, too, is something I don’t know I’ll ever be able to fully embrace. My conception of womanhood is so tied to goodness that, beyond surface-level effort—carefully shaving and grooming myself, selecting the most femme wardrobe I can, heightening my voice into the faggy upper register that’s the best I can manage for now—I constantly wrestle with the pervasive, constant certainty that I don’t deserve to be a woman. At worst, I am a man; at best, I am a simulacrum, a machine that recognizes the patterns of womanhood and carries them out with no deeper meaning or belonging than that.

But I have friends who tell me that they feel my love for them—that I’ve touched their lives through kindnesses, or given them words they needed.

And I have a partner now, someone who lives with me and holds me and tells me I’m her girl, and who says she knows I love her.

I can use she/her pronouns rather than they/them, and I can tell myself that, while I’m not good, I’m at least better than the black hole I used to be.

Eternity and the Auto-Memory Doll isn’t just Violet’s story—it’s also the story of Amy/Isabella (boy, us trans folks and characters with more than one name). And in some of the girls’ last hours together, Amy tells Violet:

“I haven’t given anyone anything.”

To which the auto-memory doll replies:

“That’s not true, Lady Isabella. You are the first to call me a friend. You taught me to hold hands and other kind things.”

I’m a copy of a person, a copy of a woman, and all too often I feel that the best I can give is a copy of kindness. But I can hold someone’s hand, and do my best to mean it, and maybe some days that’s enough.