You know the problem with customizing a box? There's no drama in it.

So, scientists thought rogue waves were a myth until 1995, when an oil rig off the coast of Norway, on an average day of thirty-foot seas, recorded an eighty-five foot wave. You can look at the recorded chart of waves that day, and it looks exactly like the chart for every other day — a steady sine pattern, a million identical peaks — with one peak that stands three times taller than the rest, starkly un-mythical, making you nervous. There was no warning. The wave before was normal, the wave after was normal, and the wave between was a tower. Fields of math were changed to reflect reality, prediction models snapped into place, and now satellites see rogue waves all the time. They're a fact of nature; behemoth vertical anomalies reminding the sky that the ocean is always coming for it.

Anyway, you can buy boxes at the craft store.

A brief word about the process of drilling holes: I knew that my Neopixels would require a 3/8" bit, and my first attempt at drilling made use of a "normal" drill bit at that diameter. Anyone following in my footsteps should know that what happens next is a supersonic collision between the box and the drill, which is a mistake that costs however much a box costs. A spade bit is the way to go for this; nice clean holes, nice sane drilling. Throw a printed grid onto the box, Sharpie a little dot through all the intersections, and nestle the spade bit into the dots. Drill, plunge, repeat.

(Continuing in the general spirit of scientific reporting, I want to provide one other key insight that was discovered along the way. Once you have a box of holes — perhaps, say, covered in sawdust and needing to be cleaned — pressing the pipe-end of a floppy vacuum hose against those holes and sliding it around creates exactly the sound of a radio being tuned. It's crazy. You're welcome, future.)

I went through over a dozen arrangements of buttons and knobs before settling on a layout; once determined, another few spade-bit holes were popped into the box and components were finger-tightened into position. The Neopixels were also temporarily added; later, I decorated each with a little black necklace of heat-shrink tubing before poking them through for good. I punched a couple holes through the side of the box for power cables, and added a giant comedy-sized "draw hasp" — that is, a latch for keeping the halves of the box locked together; one of those Pelican-case-style latches where you pull one tab over the other and it snaps down into a locking position. My giant comedy-sized toggle switch was installed next to the giant comedy-sized hasp, bringing the number of chrome-ish protuberances to two and the external assembly to its completion.

I threw an Arduino into the mix just to see what the thing would look like with the lights on, and took the photo above while in the throes of a painful grin. It was, on the one hand, totally premature to say that I had "done it" — on the other hand, it was clearly not premature to say that, and holy shit look at my glowing box.

"That looks exactly like a real thing almost," I marveled.

I cranked the brightness until it hurt. I stared into the light like a Spielberg character.

After taking the bits and pieces back out of the box and sanding everything, I treated the wood. The first thing I did was give everything a couple coats of wood stain, a sticky affair that can be affectionately thought of as kamikaze for brushes; a couple days later, now dried and pungent, the box was attacked with a fork. My idea was to give it an artful coat of faux-antique wear and scratches first, and then cover those bruises with a glaze-y finish on top, in a way that doesn't actually make sense as a replica of antique things but looks cool as sort of a "heightened reality" indulgence. I tore little nooks and scrapes into the wood on all sides, as well as re-sanding the edges and anywhere that would have been "handled" a lot over the "lifetime" of the thing. Two different kinds of damage, and I went in opposing directions with their contrast — the worn-down edges were left brighter than the surroundings, showing the original butter-colored wood instead of the stain; the scrapes and gashes were liberally gooped with black acrylic paint and then immediately wiped, leaving them dark and striking.

I went through a bunch of designs for the logo — at first I was thinking in terms of my invented relic having been a finished product that just happens to be seventy years old, and thus needing a professional period-appropriate logo that would have been professionally applied at the time and weathered since. I've done quite a bit of lettering and sign-painting stuff, and I love the look of those old "Coca-Cola"-logo style image marks, so I started merrily down the path of fanciness before coming to a sudden stop, right after sketching out my third design; my work-in-progress itself was a cooler image than the logo was going to be. The guideline rings looked wonderful with the intersecting scrapes of the text's x-height and base lines; the whole thing felt very authentic and "drawing-board"-y. I wanted to keep it, so I changed my mind: the actual (fake) history of this game was that it was a proof-of-concept that was being passed around the engineering department as a potential future-product for the company that was making it, and someone had slapped this half-assed logo on the side right before presenting the game at a meeting or something, where the company rejected the whole project and this one prototype is all that remains.

When you spend a long time on a project, you start telling yourself stories about it. Whatever. Sold.

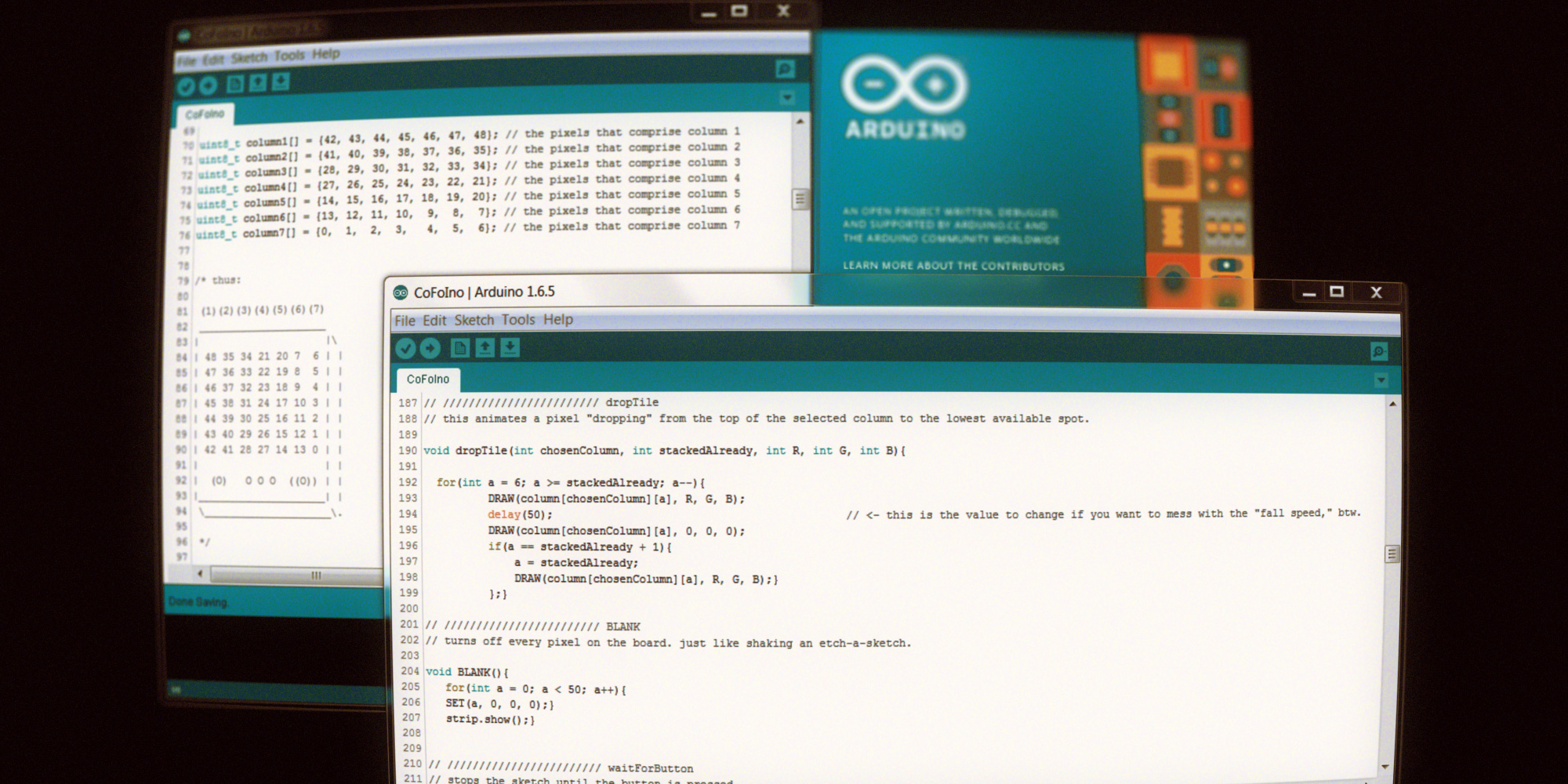

I had been calling this thing the connect fourduino in the previous weeks; I settled on the abbreviation "co-fo-ino" during the design phase because it was fun to play with the "o" shapes, and eventually arrived at the stylization CoFoiNo with the all-important minuscule "i" for the visual balance and hint that it's not a lowercase "L." I'm aware that to someone completely uninitiated it might read as "Co-Foi-No," and I have decided that I'm gonna spend the rest of my life explaining myself anyway, so what the hell.

(If I had this whole process to do over again and could only change one thing, I wouldn't add any color to the logo. Right before I applied the clearcoat, I got nervous about having the logo be totally unvarnished and penciled in a bit of color as a compromise; it still looks fine, but it looked cooler without the filled-in letters.)

I rigged up a little tripod to dangle the box from and went over it several times with clear gloss spray, maybe five or six coats in total. (I have yet to encounter a situation wherein I regretted doing too many clearcoat passes; it has always gotten better with more coats. Be brave.) I didn't do any sanding or polishing between coats, as I wanted to keep a little bit of the natural chunkiness and texture of the wood. I'd spray a coat, wait fifteen minutes, and spray again. The clear coat was the last step in the box-stylization process, and once it was dry, it still looked wet. That's the dream.

(The big red button is missing from the control surface; it adds something, I think.)

There's not much drama in customizing a box, but I think it turned out well. It was just an empty thing — the parts that were installed didn't actually do anything — but the big push and little progressions were finally getting me somewhere. It had now been several weeks since I started in on everything, and in the intervening box-time time I had begun to experiment with soldering and circuitry. I had some electrical concepts figured out; I had some electrical experience under my belt. I had the electrical components, and now I had the console. I had a plan.

All the pieces were coming together; the process of diving-in to learn the waters had turned out to be relatively safe after all. Except, fun fact — you know what's not a myth?

Teague Chrystie

I have a tendency to fix your typos.